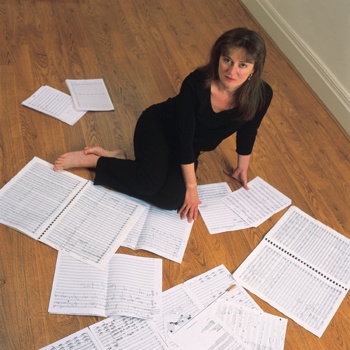

Miss Film Score: Interview with Debbie Wiseman

Originally published on Colonne Sonore-Immagini tra le Note N.12/13 - May/August 2005

Colonne Sonore meets female British composer Debbie Wiseman for an exclusive chat about her career in film music and her latest score for the French caper Arséne Lupin.Colonne Sonore: How did you start getting interested in musical scoring of cinema?

Debbie Wiseman: I love writing music for pictures, I have always been inspired by pictures. When I was at the music college I knew that i liked writing melodic music and so the natural place to write melodic music is on film and television. I decided to go in that direction. I wrote to many TV and film directors when I left the college, saying I would love to write music for their productions. After many months of waiting I got a reply from one director who liked a piece on my tape, and he said yes, come and meet me and we will have a chat, and he gave me the opportunity to write music for his film. It was a small film but nevertheless it was an important film because it meant I had the opportunity to write and work with a director for the first time. You learn on the job. At the time when I was training there weren't courses like there are now. For instance, at the Royal College of Music you can go on a film music course and study the technical side of writing music. But when I was at music college these courses didn't exist, they just weren't there. I learnt on each production a little bit more so it was very useful to have those first, very few people say "yes okay I will give you a chance".

CS: Did you study at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, was this school important for your musical development? I know you studied with Buxton Orr.

DW: He was a very great composition teacher, he was very strict and very much into orchestration, and I think that's why I like to orchestrate my own music because he taught me that when you write a melody you decide who's going to play that melody, so, for example, I may think as I am writing: I want this to be a very bold striking tune and so I put it on the brass instruments; or maybe I want the tune to be very lyrical and tender so therefore I use strings, or maybe flutes. Buxton Orr was very important to me in teaching me to understand the orchestra. He taught me how to play a scale on every instrument of the orchestra, so I know how it feels to play that instrument and this helps me to write music for it. I feel I then can translate to the orchestra what I want to hear and what the director wants to hear. It becomes a more complete vision, a more complete idea.

I understand completely why composers use orchestrators; often it's about the pressure of time. If you have a tight deadline and you have to write 50 minutes, maybe an hour of music and it's a big orchestra, sometimes there is no option. With "Arsène Lupin" there was one hundred and ten minutes of music in the score. Nearly two hours of music in the film, that was a lot. Luckily I had a good amount of time to write the score and so I didn’t need the services of an orchestrator!

CS: Really a lot of music, and what about the CD release, which parts did you decide to record on the disc?

DW: On the cd there are all the main things, 75 minutes ..so not quite all of it, otherwise it would have been a double cd at least!

CS: The music was recorded by the Royal Philarmonic Orchestra, i know you often work with them. Instead, for example, on "Tom's Midnight Garden" you worked with the Locrian Ensemble. Do you work often with this ensemble?

DW: Yes I do. They perform a lot of my film scores and televison scores. They performed on "Judge John Deed", which is a British television serial, and you see, you get to know their playing, I find I write well for them, because I know the way they play. But I also use the Royal Philharmonic a lot as well. I usually either use the Locrian or the Royal Philharmonic; it depends on the type of project. Some people prefer to have a large orchestra like the Royal Philharmonic; they like to use an orchestra that they know and have heard of, other people want something smaller and more intimate, then I may use the Locrian.

CS: Music plays different roles on a film, sometimes the music goes on background with the pictures, but other times instead, it goes against them adding a new dimension to a scene. What do you think about that?

DW: Usually on a film both are required so at times you will be expected to write music to go with the drama; for example in "Arsène Lupin" there is a scene when Arsène is on a horse and he is riding the horse chasing a train, so the music I recorded is very fast, high tempo, dramatic and definitely goes with the pictures, a lot of brass and strings; very busy.

Going against the drama is important as well on a film because at times you see on screen something very sinister, dark and perhaps you don't need to write music as sinister and dark, you want to write something else to highlight the subtext, the hidden story perhaps.

Perhaps there is a love interest there as well, or a little bit of mystery and you want to emphasise that with the music.

It's interesting because the audience will believe the music, what the music is doing, so if the scene is very innocent, and yet the music is very tense and scary the audience will believe the music, they will think something tense and scary is going to happen. So music is very powerful.

It' s important you send out the right signals to the audience. You tell them that something very scary is going to happen, or this is a very romantic moment, and the music helps the audience understand the film and enjoy it, hopefully.

CS: "Arsène Lupin" was something really different from your other works, how did you feel getting this film, how did you approach it?

DW: It was a very different film to me, my very first action adventure score and a lot of varied types of music, mystery, drama, suspense, love, darkness, in parts very moody; a wide spectrum.

CS: I think this means a lot of contrast between rest and tension...

DW: Obviously you can't have too much of one mood or one atmosphere because your ears get used to it, and then it’s not as dramatic.

So often before a very dramatic moment you will have silence or a rest or a very small pause in order that the drama of the moment that is about to follow is all the more exciting, and "Arsène Lupin" is a very good example because there is a lot of music, and we were very aware of this, so we had to be sure of the pacing. Where you really want the big moment we used choir as you can hear on the cd. There is a big choir, big orchestra, we had a 75 piece orchestra so it was a big soundscape.

There were lots of opportunities to do some action scoring, it was a huge challenge. There was a wonderful music supervisor in France called Edouard Dubois. You would get on with him so well because he is a very keen film music fan. He has a huge collection of film music CDS, the biggest collection I've ever seen, I must give you his telephone number...

Edouard was very important in the film, because he was my link to the director Jean-Paul Salome. I hadn't worked with this director before and also, I don't speak fantastic french, and he didn't speak very good english. Luckily music is a universal language! Jean-Paul temp-tracked the film. He used Bernard Herrman, some John Williams and it was great music but a bit worrying because sometimes directors can get used to the temp track and want you to copy it. But it was great because in this case they didn't, they just said: we want it to sound grand and we want it to sound exciting, but you don't have to copy the temp.

So I was given a free hand; they allowed me to write the music I wanted to. It was a great experience – definitely the highlight of my year.

I sent CDs out to Paris from time to time, for Jean-Paul and the team to listen to, and then Eduoard would call back with thoughts and comments, and the score developed in this way.

I think for me it was the most exciting film I have worked on so far, because it was such a challenge, there was so much music, it was so demanding, but in a good way, and I am really proud of the score, and the cd.

CS: In "Arsène Lupin" do you conduct by yourself the choir?

CS: In "Arsène Lupin" do you conduct by yourself the choir?

DW: Yes, i did. We had a 60 piece choir, The Crouch End Festival Chorus. They are on the CD, you'll hear them on track 10, "Countess Cagliostro". This is a fantastic choir, they are so professional, they make a great sound.

CS: The overture you wrote for the concert suite of "Arsène Lupin" is very impressive, especially the powerful and involving rythmin section.

DW: This track is the 12th, "Arsène Et Beaumagnan", that is the overture. It’s not quite the same treatment I gave the concert version because this track hasn't got such a big finish, it doesn't end because within the action of the film it is a big fight sequence and at the end the music is leading the audience to the next event – the aftermath of the fight. In concert you need to finish the piece. So I had to just slightly re-work it, so we'd come back to the main theme at the end.

CS: And what about animated films? Would you like to score an animated film?

DW: I’ve already scored one, but you would probably haven't seen it because I doubt if it has been in Italy yet, the "Oscar Wilde Fairy Stories". I must get you a copy! They are animated so beautifully, and I wrote the music before I saw the finished film, which is the way it usually works in animation because the editors need to cut the action to the music.

CS: You have really a great gift in melody writing, how do you keep your creativity so fresh?

DW: I think one of the great gifts of being a film composer, is you always have an inspiration from the film, the television program or a character. And that keeps you fresh and gives you inspiration. For example with "My Uncle Silas" he is a wonderful, lively character, and that helps me to compose melodic tunes for him.

I generally like to start with creating a theme for the character or a strong melodic line that would help me write the score. When I get that, usually the rest of the score flows naturally, but for me it all starts from that one little hook, that little phrase or three or four notes...

CS: Do you usually compose something every day?

DW: I always compose every day. Usually it's for what ever I am working on. I like to just keep writing because that helps me keep fresh. if I stopped for two weeks I think I might have trouble when I started again!

I like to keep just ticking over and writing a lot, and i love writing so it's not a problem to do it. I think you use a different part of your brain for music than you do for anything else. I feel I have to keep that fresh, so I have to keep writing as much as I can every day.

If i am on a great film with great characters then the tunes come very easily. The only problem is when I'm on a film that I can’t immediately get inspiration from, and maybe it is difficult to find the musical language or the route to take, and then I struggle and I have to go out for a walk or have a swim or do something completely different, go as far away as possible from the piano.

CS: How many times the music you compose is really the music you would like to write?

DW: That’s a very good question. I think in some ways it’s good to consider the requirements of a film, because it focuses your composition and you think: I have to write in this particular style because this is what the film needs.

Therefore when I am writing for a film I don't think to myself: "would I like to write something else?" I write what I think is right for the film. Sometimes, of course, what I think is right, what I would really love to write for the film, is different from the director’s idea, so then i have to reshape my own mind in line with what the director wants, to try and understand what it is he wants to convey musically. And then I do have to adapt my feelings about what the music should be, and in fact I've had to do that a few times; but mostly I would say what I want to write is what ends up in the film. Not always, but mostly. That's the best you could hope for as a film composer.

But I also would love one day to write music that truly stands alone, not associated with a film, music that just comes from me and not on the back of a character or a storyline - I would love to write a piano concerto for example. I love playing the piano because I've studied piano all my life, and therefore this is the instrument I understand most, and feel most comfortable writing for.

But when I would have time to do that - a few years time or ten years time - I don't know, but it would be the music that I want to write for a concert, maybe for a pianist that I love.

CS: What about when you are spotting a film, what are the things you really look for?

DW: Dynamic points, really; that’s the best way of describing them – moments that demand music. But again, it depends on the type of film. It’s easy to say there should be music every time people kiss, or when someone gets shot, or when the hero jumps on a horse and chases the train, but it’s not always the case. Each show has its own individual needs, and the first thing I try to do is understand what the director is saying with every shot and every line of dialogue, and work out the best way to mesh in with the pictures and the sounds.

CS: What' s your composition method? Do you write with paper and pencil or you use a synth?

DW: I started in the business a couple of years before the advent of the personal computer age, and so when I got out of college I continued initially the way I learned; with paper and manuscript paper. As I progressed and technology also progressed I incorporated computers into my work, and now I have pretty much everything I need to orchestrate the music, lock it to picture and print out my scores and parts; but even today I still start by scribbling down the top line onto a piece of paper before I play the music into my system!

CS: What do you think makes a great score? Which things make a score stand out in your mind?

DW: It’s very hard to define what makes a “great” score; there are many different opinions. Some like minimalist scores that creep around the edges of the action; others favour grand sweeping scores. Sometimes a good film can be devalued by a dull formulaic score; similarly, a wonderful score can be sunk without trace by the fact that the film is awful. I suppose, however, that it’s universally true that a great working relationship between a composer and a director on a great film makes a great score.

CS: Let' s talk for a while of a recording session. Do you use click tracks or do you prefer punches and streamers? Are you using "Auricle" film music system?

DW: I use click tracks and I map them out myself. I’ve never used streamers. I find I have more flexibility for changing the music to a new cut of the film before the recording day if the click track is under my control. I use a software program called CADENZA for my click tracking and picture lock. No-one’s ever heard of it and I think they’ve stopped making it now – at least no-one’s ever sent me an upgrade! – but I love it; no other program I’ve come across since gives me such flexibility with my sampler note placement and MIDI file compiling.

CS: How do you feel when you go to the recording session, when you hear for the first time the music you wrote? Do you use to test it before with some synthesizers?

CS: How do you feel when you go to the recording session, when you hear for the first time the music you wrote? Do you use to test it before with some synthesizers?

DW: I’ll answer that two-part question in reverse order, if I may! I do make a mock-up of all the cues I write on CADENZA, linked up to samplers – not synthesizers, I must emphasise – samples are actual recordings of real musicians playing real notes, so the authenticity is much greater and although the true dynamics are not there in these recordings, it’s very useful for me as I orchestrate my scores. I also use these files to play to directors as the composing process goes on, so they can get a very good idea of what the cues sound like against picture.

As to the first part of your question, the feeling I get when I hear my music played for the first time by a real-life orchestra is almost indescribable. It’s a sense of true elation at the fantastic sound the musicians make. It’s what I’ve been working towards, and it’s always very rewarding to hear all the hard work come to fruition in the studio.

CS: Can you tell something about making the music of “Wilde Stories” (the Oscar Wilde’ s Fairy Stories)? Do you take a different approach to scoring animation?

DW: This was a wonderful project that initially started with the head of Warner Classics hearing my score for the 1997 film WILDE. He liked the music and wanted to make a CD album of Oscar Wilde’s fairy stories set to music, in the same vein as PETER AND THE WOLF. In 2000 we recorded two stories, THE NIGHTINGALE AND THE ROSE and THE SELFISH GIANT, with Vanessa Redgrave and Stephen Fry narrating. This CD did well and was nominated for a Grammy award. Then Jan Younghusband, the commissioning editor of Channel 4 here in the UK, heard the album and came up with the idea of animating three of Oscar Wilde’s fairytales. We added THE DEVOTED FRIEND to the list and I started writing at the same time as the animators were sending me drawings and storyboards. I composed THE DEVOTED FRIEND from scratch, and adapted, extended and reworked the other two scores to suit the length and mood of the animations. It took nearly a year and a half to complete the animations and finish the music, as we were developing the two side by side – and this is what is different about scoring for animation! - and we recorded the music in the summer of 2002 at Grouse Lodge,a lovely studio in the heart of the beautiful Irish countryside. It was a very memorable time.

CS: You recently worked for a film, the now completed british film "The Truth About Love", directed by John Hay, it's a 100 min motion picture...can you tell us a little about that?

DW: This is a British-made romantic comedy starring Dougray Scott and Jennifer Love Hewitt. It’s about a woman who sets out to prove to her sister that her husband would never cheat on her, in a very unusual way. I’m not saying any more than that or I’ll give half the plot away – you’ll have to go and see it when it comes out! The approach to the score was very interesting – I made the main theme basically a passionate dance between the two main characters, and another theme reflected the alternative love interest – solid, reliable… but again, I don’t want to give the story away! I loved doing the film, though… it was a big contrast in style to ARSENE LUPIN. I like to keep my work as varied as I can.

CS: What would be your advice for the young film music composers?

DW: I‘d suggest that they send their showreels out to every production being made, and keep sending them out, writing the letters and emails, keep knocking on the doors. If you’re any good, there will be somebody who’ll want to work with you, and keep working with you.

Special Thanks to Debbie Wiseman for her kindness.