18 Mag2017

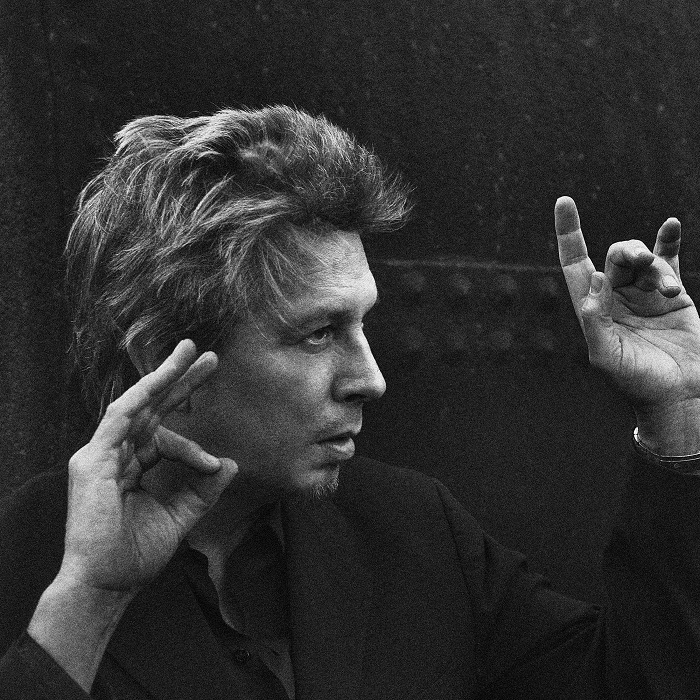

A Triple Life: Interview with Elliot Goldenthal

Elliot Goldenthal is one of the most original and unique voices working today in film and concert hall. His works for films such as Alien 3 (1992), Interview with the Vampire (1994), Heat (1995), Batman Forever (1995), Titus (2000), Final Fantasy (2001), and the Academy Award-winning Frida (2002) are among the best film music written in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Despite his apparent absence from the proscenium of big-budget Hollywood films in the last few years, the composer is more productive than ever in several different mediums—on the concert stage, his Symphony in G# Minor was premiered a couple of years ago by the Pacific Symphony Orchestra, while a new composition called “Waltz and Agitato 'Pravda'” was recently premiered by the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in Eastman, NY. Goldenthal also wrote an original score for the play Grounded, starring Anne Hathaway and directed by his frequent collaborator Julie Taymor. Goldenthal also composed an original score for Taymor's direction of William Shakespeare's A Midsummer’s Night Dream that debuted in 2013 at the Theater of New Audience in Brooklyn, NY. The play was then filmed by Taymor with cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto and released in limited theaters in 2015. For this filmed version, Goldenthal wrote and recorded a new score to accompany Taymor's phantasmagoric and strikingly original setting of Shakespeare's immortal piece. Finally, Goldenthal released a lot of his concert and stage works on his own independent record label (Zarathustra Music).

Despite his apparent absence from the proscenium of big-budget Hollywood films in the last few years, the composer is more productive than ever in several different mediums—on the concert stage, his Symphony in G# Minor was premiered a couple of years ago by the Pacific Symphony Orchestra, while a new composition called “Waltz and Agitato 'Pravda'” was recently premiered by the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in Eastman, NY. Goldenthal also wrote an original score for the play Grounded, starring Anne Hathaway and directed by his frequent collaborator Julie Taymor. Goldenthal also composed an original score for Taymor's direction of William Shakespeare's A Midsummer’s Night Dream that debuted in 2013 at the Theater of New Audience in Brooklyn, NY. The play was then filmed by Taymor with cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto and released in limited theaters in 2015. For this filmed version, Goldenthal wrote and recorded a new score to accompany Taymor's phantasmagoric and strikingly original setting of Shakespeare's immortal piece. Finally, Goldenthal released a lot of his concert and stage works on his own independent record label (Zarathustra Music).

We talked with Elliot Goldenthal about the soundtrack album release of A Midsummer’s Night Dream, while also touching on several other topics.

ColonneSonore: Let’s start talking about your new work, William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer’s Night Dream. The album you recently released is the soundtrack for the film version of the stage piece that you and director Julie Taymor did together in 2013 for the Theater of New Audience in Brooklyn, NY. Can you give us a bit of background information about how the piece was born and how it ended up being produced as a film version?

Elliot Goldenthal: It was an idea that Julie Taymor had. She wanted to have a filmic experience [of the stage version]. When you’re sitting in the auditorium as an audience member watching a Shakespeare’s play, you only see it from one angle and the language is very difficult, so you usually focus on the character who is speaking. In the movie, Julie had the ability to show reaction shots, as well as medium shots, long shots, etc, so you’re able to see the interaction with characters more than you would as an audience member. You can move around the theatre and around the point of view of the camera—high shot, below, looking up, but especially you see reaction shots. Julie had so many [of those], like a normal film would, and that gave me the opportunity to write completely new music because [the new shots] generate different emotions throughout the movie.

CS: So did you change or add a lot in comparison to the original score you wrote for the stage version?

EG: Yes, I would say I wrote 30 percent more. It was mainly because in the theatre version I may have an 8-minute scene with an environmental piece that’s not supposed to hit any cues, it has just to be there and work with the actors as a sort of musical environment. But that changes when you have a filmed version. On a film you have to be very specific, so all the music which was non-specific had to be changed and tailored for specific shots and movements.

CS: The music of the film version is very subtle and atmospheric, it has a lot of interesting textures and dark colors. I noticed a particular use of glass harmonica.

EG: Yes, I use it very often, especially in film. I use also crotales, bowed metal percussion, bowed vibraphone, bowed marimba etc. because I find that those sounds don’t interfere with the dialogue and they are also not as expressive as strings are, although they’re not as cold as string harmonics. So I find it very useful instruments to use in combination with the dialogues.

CS: Talking about the dialogue, how much Shakespeare’s words and meters and their inner musicality influenced your writing?

EG: Well, it’s mainly dancing between the raindrops, in the sense that the composer is best to stay out of the way of Shakespeare and also stay out of the way of the performance of the actors. As difficult that is, you almost have to find something to support the actors’ performance, so you don’t have to conflict with the meters. In A Midsummer Night's Dream of course I had a number of songs to work with. Not all the songs are on the album, but you can see and hear them in the film. In those songs I had to be very respectful to the meter.

CS: This project is a very interesting and unique piece. I’d define it a very interesting hybrid given its origins and development. Hybrid, for me, is also a way to describe your general work, for both film, theatre and the concert hall. You have a very unique and diverse voice.

EG: It only feels that way because I think we’re now in the period where we’re alive. If you advance the time a hundred years, it would all feel as it’s kind of coming from the general period. Even if I’m harking back to earlier periods like Renaissance or 18th century here and there, it still feels like a 20th century composer doing that. When you listen to Mozart’s piano sonatas, for example, it sounds like 18th century music, apparently. Upon closer inspection, you can see that it’s not just 18th century style, but it borrows from different periods, from earlier composers like Bach, Gabrielli and so on. It borrows from music from Italy, Spain and Germany, it’s not just Austrian. During those days you may find Italian melodies in a Mozart piano sonata, just giving one example, because that was probably a big thing for composers in the 18th century. But looking back now, it all seems like one voice, one period of music. So I think it’s the same with me. The farther you get from this time, the more you will probably feel [my music] is representative of my period of composing, i.e. mid-late 20th century/early 21st century.

CS: Speaking about periods of music and spheres of influences, I always thought that 19th century symphonic music of German composers like Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss and 20th century Polish avant-garde style of composers like Krzystof Penderecki were pretty big influences in your work, both in film and concert hall. Your music seems like a cross between these two worlds.

EG: I especially like that period of 19th century German composers, Wagner, Mahler and so on. I like their approach to how they work with the concept of time, especially with string orchestras. They could suspend time differently than other composers were doing at the same period. Especially late Mahler, the last movement of the 10th symphony, especially that idea of suspending time in a way that is beyond the voice, it’s beyond usual technique of the length of the string related to the bow. It was a beautiful thing to me that Wagner started in Tristan and Isolde and Siegfried and things like that, and Bruckner of course explored as well. So that part of the world, that particular technique or expression, as opposed to the notes of the chords, especially in the use of the strings, I found it very inspirational.

Of course growing up in the 20th century New York City surrounded by John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Jimi Hendrix and everyone else living through jazz, pop and rock music meant a lot for me. It's a big rhythmic influence on my music, so I’m very at home with those genres as well and that might be represented in a film like Titus.

As far as 20th century Polish avant-garde, Penderecki in particular, I'd say that his use of aleatoric notation is very significant because, on a practical level, if a composer had to write those dissonances and interlocked rhythms down exactly the way they are, it would be too difficult to rehearse. Penderecki found a way that includes the musicians slightly improvising, but in a very controlled way. The use of clusters in the strings and the brass is extremely influential throughout middle and late 20th century until now, actually.

Of course growing up in the 20th century New York City surrounded by John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Jimi Hendrix and everyone else living through jazz, pop and rock music meant a lot for me. It's a big rhythmic influence on my music, so I’m very at home with those genres as well and that might be represented in a film like Titus.

As far as 20th century Polish avant-garde, Penderecki in particular, I'd say that his use of aleatoric notation is very significant because, on a practical level, if a composer had to write those dissonances and interlocked rhythms down exactly the way they are, it would be too difficult to rehearse. Penderecki found a way that includes the musicians slightly improvising, but in a very controlled way. The use of clusters in the strings and the brass is extremely influential throughout middle and late 20th century until now, actually.

CS: I guess this technique of playing with time, making things faster or slower than they appear, works very well when you’re writing for film, which is an art that surely involves time at its core.

EG: Yes, and again, when you have long sostenuto (i.e. sustained, ed.) passages, they don’t interfere with the dialogue. It doesn’t bring attention too much to the editing.

CS: That’s fascinating. Talking about your artistic relationship with Julie Taymor. You have done a lot of work together and your bond is very strong. How your collaboration evolved through the years in terms of methods of work, exchange and mutual influence?

EG: She’s a very inspirational person, I mean in the sense she gets very personally involved and excited in the projects she does. She loves to involve music from the very beginning and she’s very attached to music in a very intellectual way, but also in a very physical way. When you see her direction of both my works and other composers like Stravinsky, Wagner, Mozart, she’s very sympathetic to the cadences and allow her to support the music, so the audience has a visceral connection to the music. It’s remarkable especially when I watch her direct operas or musicals with other composers involved, like The Lion King.

CS: Throughout all your career, you worked in several different mediums: film, concert hall, theatre, ballet. You always had a very diverse career, so I guess you never suffered with the “double life” syndrome…

EG: I have a triple life! But that was normal for most composers, you know. My teacher for example, John Corigliano—he has very healthy life in concert music and opera as well as film. Philip Glass has a very healthy life in various media, including theatre, concert works and soloist work. Aaron Copland, my other teacher, also composed for film, concert stage, opera and ballet of course. That is the environment I grew up with and was taught by, so it seemed natural to me that’s what the job of the composer is.

CS: It’s all about the music, in the end.

EG: Yeah, it’s also all about where you’re wanted at the time. Composer has to go where he or she is wanted, otherwise there is not enough use in your life.

CS: I guess when Miklòs Ròzsa talked about the syndrome of the double life, it was probably something he felt during his time. Composers like him or Bernard Herrmann struggled to see their own concert music properly received and perhaps they used their film work to establish a name and get their more “serious” music performed.

EG: That might be true, but they really loved working in film. They really loved it. One thing we forget about Bernard Herrmann is that he was also a conductor and he conducted a premiere of a new composition by another composer almost every month on his radio show. He was always conducting new music. He was very open and very involved. He was a creature of creating music on the spot as an artist. He didn’t like recorded music, he believed music was a living thing and it had to be performed live and heard live.

CS: What can you tell us about your future projects?

EG: I guess I live a double or a triple life, so I’m writing right now a Trumpet Concerto that’s premiering in Philadelphia on October 1st. I’m about to sign for a movie, but I can’t go into detail now. It’s being released in November. Also, with Julie there’s always a project we’re constantly doing. We'll do a theatre version of [David Henry Hwang's] M. Butterfly. I’m writing a new score for that and it will premiere this fall on Broadway, with Clive Owen in the main role. So by the end of the year these three works will be released.

CS: Are you working on concert adaptations of your film music as well?

EG: Yes, that usually comes up when festival are requesting something. I had occasions to present some of my music for film at the beautiful festival in Krakow, Poland, as well as in Ghent, Belgium, I love that festival. So when the occasion comes up and the practicality is there, I love to adapt my film pieces for concerts.

CS: Thank you very much for talking with us, Elliot.

EG: Thank you!

Special thanks to Jeff Sanderson (Chasen & Co.) and Jonathan Zautner (Zarathustra Music) for their help and support in setting up the interview. And a heartfelt thank you to Elliot Goldenthal for his kind friendliness.

The photo portraits of Elliot Goldenthal are by Marco Guerra. Used with permission.

Official Website: http://elliotgoldenthal.com/